10 Questions With…Abeer Seikaly

Amman-based Jordanian-Palestinian designer and architect Abeer Seikaly has always placed craft and heritage at the forefront of her practice, seeking to bridge the gap between age-old traditional design and contemporary aesthetics.

Her work traverses design rooted in indigenous Bedouin skills, multi-use disaster shelters for refugees and collectible design for people craving the beauty of handmade craftsmanship. Many of her projects take inspiration from the Jordanian desert, where she engages in Bedouin women’s craftsmanship of textile weaving. “Craft, to me, is a mindset,” she tells Interior Design, “a commitment to infusing every project with care, intention, connection, authenticity, and reverence for tradition, as I witnessed in my family’s craft.”

In 2010, Seikaly directed Sunny Art Fair, the first contemporary art fair in Jordan, and co-founded Amman Design Week in 2016 alongside Rana Beiruti, helping put an international spotlight on local design. Her works have been exhibited at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo’s Miyake Issey Foundation, Sharjah’s Barjeel Art Foundation and others.

Most recently, Seikaly won the Craft category of the inaugural Design Doha Prize, receiving 100,000 QAR (approximately $27,500 USD) to sustain her practices, as well as mentorship support from international designers and industry experts, as well as other benefits.

Abeer Seikaly Talks Craft + Bedouin Influence

Interior Design: How did you first get started in the design and architecture world?

Abeer Seikaly: When I was five years old, my father’s friend and architect, Akram Abu Hamdan, brought an architectural model he had made to our apartment. It was a model of our future house. Over the next two years, I watched this miniature version gradually transform into the actual space we now inhabit, with my father leading the construction efforts. This memory dwells within me wherever I go; it sparked my interest and connection to the creative process and instilled within me a deep respect for building and construction. Beyond the model’s physical presence, this experience taught me that every blueprint and model holds the promise of translating an idea into reality.

It wasn’t until 9th grade, in an IGCSE class named Craft, Design, and Technology, that my design awareness truly began to form. This class taught me problem-solving through creativity, planning, and design. I honed skills like resourcefulness and critical thinking while learning to work with various materials and tools. It also emphasized the importance of effective communication in the design process, providing a solid foundation. My final achievement in the class was designing and constructing a family house extension, where I earned the highest mark worldwide. This recognition motivated me and solidified my determination to pursue design for the rest of my life.

ID: Craft plays a large part in your practice—what first drew you to this form of design? What kinds of craft do you design with?

AS: Craftsmanship has always been central to my upbringing and practice. From a young age, I observed my grandmother and mother creating beautiful things from scratch, transforming materials into works of art. It wasn’t just about making objects; it was about connecting with each other and our surroundings. Their commitment, dedication, and hard work have inspired and made me curious about the stories behind each creation. As I grew older, I found myself drawn to the expressive potential of various mediums and the nuanced ways in which materials could evoke emotion and meaning. This curiosity led me to Jordan’s Badia desert, where I discovered the rich traditions that defined my family’s way of life.

Historically, women wove their homes, known as Beit al Sha’ar, using locally available materials and tools, with the craftsperson’s body being a vital instrument in the creative process. The site of making was intrinsic to the final product, with materials sourced from indigenous animals and tools reflecting the surrounding environment. These principles and connections guided my practice through engaging with cultural heritage. In today’s world, where technology often dominates our lives, redefining the idea of craft is more important than ever. It’s about reclaiming the human element in design, embracing imperfections that make each creation unique, and honoring the traditions passed down through generations.

ID: How do you approach updating or incorporating traditional craft into contemporary design?

AS: It requires a nuanced approach that I adhere to through the concept of circularity, which combines the past, present, and future into a continuous cycle. Grounded in my Palestinian-Jordanian heritage, I perceive tradition not as a relic of the past, but as a living force that shapes our collective identity and informs modern practices. This belief forms the foundation of my creative process, which is guided by a metaphorical “creative compass.” This compass helps me navigate the complexities of today’s world and consider various socio-cultural, environmental, technical, and economic factors.

The “creative compass” represents a reflexive praxis, acknowledging that as designers, we are not detached observers but subjective actors impacted by and impacting our surroundings. By continuously circling back to this epicenter, I delve deeper into my process, practice, outcomes, and choices. This approach fosters a comprehensive understanding of design, guiding me to create works that resonate with contemporary society while repurposing and honoring traditional craft in a meaningful and sustainable manner. This concept of circularity acknowledges the cyclical nature of cultural evolution and the interplay of ideas and practices, enriching the dialogue between tradition and innovation in contemporary design.

ID: How did your time spent learning from local Bedouin craftspeople in Jordan influence your work?

AS: They taught me many things. One of the things that continues to resonate with me is that even in tough times, creativity can thrive. The Bedouins see the desert as a provider and adapt to survive through collaboration and resourcefulness. Learning from their heritage, passed down through generations, teaches us to make the best of what we have, especially in tough times. This wisdom inspires us to think creatively when faced with challenges.

Flexibility is key. Like the Bedouins, I see scarcity as a driver for creativity, pushing me to think differently about the world. I’m always asking how creative thinking can address the issues we face today and change our views.

ID: I understand your work often has connections with social initiatives, like your projects Weaving a Home and Terroir. Please tell us about these projects.

AS: Weaving a Home (2013–ongoing) reimagines shelters for displaced communities, drawing inspiration from the traditional Bedouin tent, known as Beit al Sha’ar. The lightweight structure combines local materials and new construction methods to create a technical, structural fabric. The stable double membrane enclosure offers dignified living conditions while harnessing renewable energy and collecting water. Acting as a decentralized energy system, Weaving a Home is resilient and energy independent, with potential applications in diverse building typologies. Beyond providing physical shelter, it operates as a social instrument, empowering communities to address modern housing challenges and enhance social cohesion. Developed in cooperation with renowned London-based engineering firm Atelier One, the project has evolved into a feasible structural realization and an innovative prototype design ready for production.

In my architectural practice, I challenge the notion of permanence, considering not only the physical and material aspects but also the cultural and ecological impacts of buildings. This philosophy is embodied in Terroir (2022–ongoing), a mobile art pavilion that honors Bedouin culture, locality, and traditional knowledge and practices. Through traditional weaving techniques and contemporary design, it creates immersive experiences. Hand-woven on a traditional ground loom by 14 women of the Howeitat tribe using locally sourced wool, Terroir represents cultural inheritance and inherent qualities of the land. It fosters collaboration and connection, encouraging engagement with the land, materials, and each other. As part of a community-led initiative in Jordan’s Badia desert, the project advocates for social and environmental consciousness while supporting Bedouin women and upholding indigenous wisdom.

ID: In 2018 you established ālmamar, a cultural experience and residency program based in Amman—what are the aims of this program and how important is it to support the local craft/design scene?

AS: The primary aim of ālmamar is to provide a platform for communal building and cultural practices through the repurposing of abandoned buildings and the adaptation of cultural traditions. It operates within the “Cultural Shell,” a building dating back to 1949 located in Amman’s historic neighborhood of Jabal Al Weibdeh. ālmamar seeks to challenge the conventional approach of “program seeks building” by reversing it to “building seeks program.” Through interactive exhibitions and events, ālmamar aims to foster creativity, critical arts practice, and the exploration of traditional values within the context of Jordan. Furthermore, ālmamar plays a vital role in supporting the local craft and design scene by providing opportunities for experimentation, innovation, and the revitalization of urban spaces.

ID: Having just won the Craft category for Design Doha Prize, tell us about the projects you presented to the judges.

AS: The various projects I presented, and the different phases of their development over the years, highlight the significance of repurposing and reappropriation as a necessary precursor to advancing new, more sustainable modes of artistic expression, architectural production and design thinking.

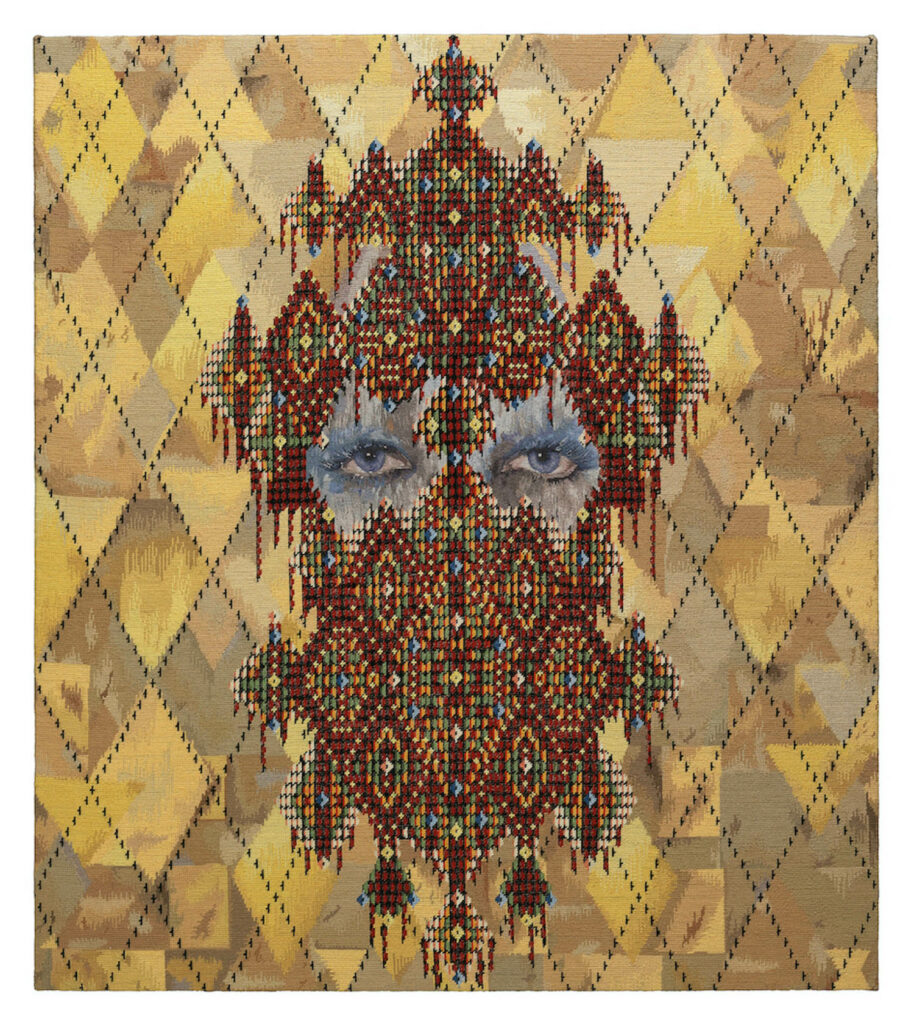

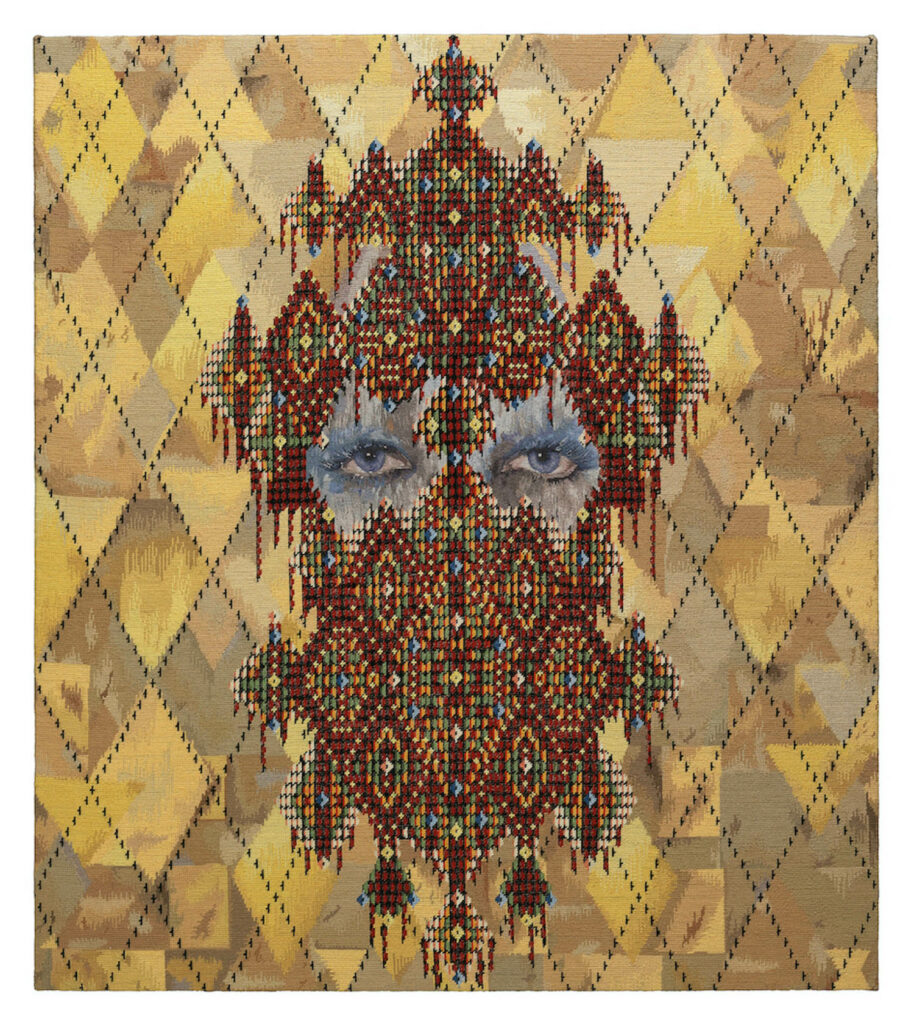

Among these projects was Meeting Points 1.0 (2019-ongoing), which combines traditional Bedouin and contemporary design practices within a multi-layered structure that is both a work of art and a prototype for temporary dwelling. Engaging over 60 rural and Bedouin community members from various governorates across Jordan, the project fosters social, cultural, and economic development, with a particular focus on empowering women within these communities.

ID: What will you do with the prize money?

AS: The prize offers an opportunity to further refine adaptable material systems and sheltering solutions through collaborative efforts. It will also support the development of a sustainable fiber-based processing industry, along with a program for local resource management, training, and community development to empower Bedouin women.

Regarding future projects, I’m currently working on a mobile art pavilion that expands on the concepts from Terroir. This project merges Bedouin cultures from Jordan and the Gulf region to create immersive cultural experiences. Originating in Sharjah, UAE, the project was co-commissioned by the Sharjah Architecture Triennale under curator Tosin Oshinowo. As part of the same community-led initiative in Jordan’s Badia desert, it supports Bedouin women and preserves indigenous wisdom while sustaining time-honored design within the canons of contemporary—and future—design in the Arab world.

ID: How do you hope the mentorship program and exposure will impact your work?

AS: Facing the urgent humanitarian crisis of displacement, with millions fleeing violence or natural disasters, humanity finds itself at a pivotal juncture in its evolution. Despite transitioning from nomadic to sedentary civilizations, global factors such as rapid population growth, urbanization, political unrest, and climate change are reshaping our lifestyles, pushing us towards a more nomadic existence. To address these challenges, we must integrate diverse fields of knowledge and draw from the vast pool of human experience to innovate shelter solutions.

Collaborating with a global community is essential for fostering new approaches to living in the 21st century. This collective effort reflects the unity of human connections and the beauty of cross-cultural creativity. By leveraging diverse expertise, my research aims to analyze how material and technological innovation can be woven into social and cultural environments to address displacement challenges effectively.

ID: Your recent light piece Constellation 2.0: Objects. Light. Consciousness shown at Arab Design Now—the headline exhibition of Design Doha—combines many different techniques and forms of design. Tell us about the piece.

AS: Constellation 2.0: Objects. Light. Consciousness. is an artwork, rather than a product. It’s a suspended light sculpture that is handcrafted from over 5,000 kiln-casted Murano glass pieces. Drawing upon Arab and Italian heritage, it merges traditional Bedouin weaving with Venetian glassmaking.

This is the second iteration in a series of functional light sculptures that explore fundamental patterns, evolving materials, and diverse spatial experiences and is the successor to the prototype, Constellations 1.0 (2013).

A decade of development and experimentation with various materials and scales led to Constellations 2.0. Through continuous refinements, I crafted a stretchable glass mesh that transitions from physical materiality to light. When illuminated, its Murano glass body projects a pigmented display. It is reminiscent of a starry night sky in the wilderness of the desert. As a cross-cultural work, the piece is a meeting point of different cultures, influences, and practices that go beyond borders.

read more

DesignWire

Behind the Mic: Get to Know Jeremiah Brent

What does Jeremiah Brent, interior designer and host of the Ideas of Order podcast, have to say about home? It turns out, quite a lot.

DesignWire

Design Icon and Hall of Famer Gaetano Pesce Dies at 84

Gaetano Pesce, a visionary designer, artist and sculptor who enchanted the world with his unique sense of materiality, has passed at 84.

DesignWire

Step Into The Artistic Glamor of Gardiner House

Inside the Gardiner House, a luxury harbor-front hotel that nods to Howard Gardiner Cushing in Newport, Rhode Island, by Herk Works and Space Exploration.